Introduction: The Unsung Heroes of Composting

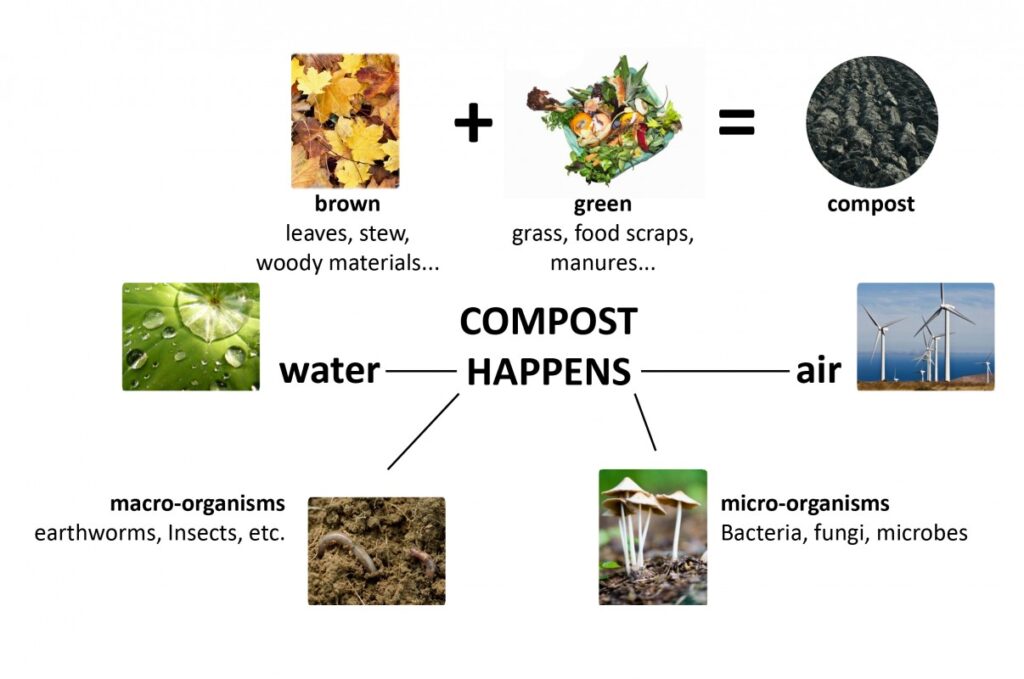

Composting, at its heart, is nature’s way of recycling. But it’s not a solitary process. It’s a vibrant ecosystem teeming with life, and the most crucial players are the native decomposers. These are the organisms – bacteria, fungi, insects, and worms – that break down organic matter into nutrient-rich humus, the black gold that feeds our gardens. Attracting these decomposers isn’t just about throwing kitchen scraps into a pile; it’s about creating an inviting habitat where they can thrive and do their vital work. Without them, your compost pile will be a stagnant, smelly mess. But with them, it will transform into a powerhouse of fertility.

Imagine your compost bin as a bustling city. The decomposers are the sanitation workers, tirelessly cleaning up the organic waste. The more workers you have, and the happier they are, the faster and more efficiently the city runs. Our goal is to become master city planners, designing and maintaining the perfect environment to attract and retain a thriving population of these invaluable decomposers. This guide will equip you with the knowledge and practical tips to do just that.

Understanding Your Decomposer Workforce

Before we can attract decomposers, we need to know who we’re trying to attract. The composting world is diverse, with different organisms preferring different conditions. Let’s meet some of the key players:

Bacteria: The Microscopic Powerhouses

Bacteria are the first line of defense in the composting process. These microscopic organisms are responsible for the initial breakdown of organic matter, especially during the thermophilic (hot) composting phase. They thrive in warm, moist environments with a good balance of carbon and nitrogen.

Fungi: The Filamentous Network

Fungi are incredibly important for breaking down tougher materials like wood, cardboard, and paper. They spread through the compost pile in a network of filaments, secreting enzymes that decompose these complex substances. Fungi prefer slightly acidic conditions and are more tolerant of drier conditions than bacteria.

Worms: The Soil Engineers

Worms, especially red wigglers (Eisenia fetida), are composting superstars. They consume partially decomposed organic matter, further breaking it down and enriching it with their castings (worm poop). Worms aerate the compost, improve drainage, and distribute beneficial microbes. They prefer a moist, dark environment and a steady supply of food.

Insects: The Diverse Crew

A variety of insects can contribute to composting, including soldier fly larvae, springtails, and beetles. Soldier fly larvae are particularly voracious eaters, capable of breaking down large quantities of organic matter. Springtails help control fungal growth, while beetles assist in shredding materials. Each insect has its own preferences, but generally, they prefer a moist, sheltered environment.

The Key to Attraction: Creating the Ideal Habitat

Attracting native decomposers is all about creating the right conditions for them to flourish. This involves managing several key factors:

1. The Carbon-Nitrogen Ratio: The Perfect Meal

Decomposers need a balanced diet of carbon and nitrogen to thrive. Carbon-rich materials (browns) provide energy, while nitrogen-rich materials (greens) provide protein. An ideal carbon-nitrogen ratio is around 25:1 to 30:1. Too much carbon, and decomposition will be slow. Too much nitrogen, and the compost will become smelly and anaerobic.

Examples of Carbon-Rich Materials (Browns):

- Dried leaves

- Shredded cardboard

- Newspaper

- Straw

- Wood chips

Examples of Nitrogen-Rich Materials (Greens):

- Grass clippings

- Kitchen scraps (vegetable and fruit peels, coffee grounds)

- Manure

- Green leaves

- Weeds (before they go to seed)

Balancing the carbon-nitrogen ratio is an art, not a science. A good rule of thumb is to add about twice as much brown material as green material. However, this can vary depending on the specific materials you’re using. Observe your compost pile and adjust the ratio as needed. If it smells bad, add more browns. If it’s not heating up, add more greens.

2. Moisture: Keeping it Just Right

Decomposers need moisture to survive and function. However, too much moisture can lead to anaerobic conditions, which will kill off beneficial organisms and produce foul odors. The ideal moisture level is about 50-60%. The compost should feel like a wrung-out sponge. If you squeeze a handful, a few drops of water should come out.

To maintain the right moisture level:

- Water the compost pile regularly, especially during dry periods.

- Cover the compost pile to prevent it from drying out too quickly.

- Add dry materials (browns) if the compost is too wet.

- Turn the compost pile regularly to aerate it and prevent it from becoming waterlogged.

3. Aeration: Breathing Life into Your Compost

Most decomposers need oxygen to survive. Anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen) will favor the growth of undesirable bacteria that produce foul odors and slow down decomposition. Aeration can be achieved by:

- Turning the compost pile regularly (every few days or once a week).

- Using a compost aerator to create air channels in the pile.

- Adding bulky materials (like wood chips or straw) to create air pockets.

- Ensuring the compost pile is not too compacted.

Turning the compost pile is the most effective way to aerate it. This not only introduces oxygen but also mixes the materials, ensuring that all parts of the pile are exposed to air.

4. Temperature: Finding the Sweet Spot

Composting can occur at different temperatures, depending on the types of decomposers present. Mesophilic composting occurs at moderate temperatures (68-104°F or 20-40°C), while thermophilic composting occurs at higher temperatures (104-160°F or 40-71°C). Thermophilic composting is faster and more effective at killing pathogens and weed seeds, but it requires more management.

To achieve thermophilic composting:

- Maintain a good carbon-nitrogen ratio.

- Ensure adequate moisture.

- Turn the compost pile regularly.

- Have a large enough compost pile (at least 1 cubic yard).

The heat generated by thermophilic composting is a sign that the decomposers are working hard. However, if the temperature gets too high, it can kill off beneficial organisms. Monitor the temperature with a compost thermometer and adjust the conditions as needed.

5. Particle Size: The Easier to Chew, the Better

Smaller particle sizes provide a larger surface area for decomposers to work on. Shredding or chopping materials before adding them to the compost pile will speed up decomposition. This is especially important for tougher materials like leaves, cardboard, and wood chips.

You can use a shredder, lawnmower, or simply chop materials with a shovel or knife.

6. pH: Keeping it Neutral

Most decomposers prefer a neutral pH (around 7). Highly acidic or alkaline conditions can inhibit their growth. You can test the pH of your compost with a soil pH meter or test kit.

To adjust the pH:

- Add lime to raise the pH (make it less acidic).

- Add sulfur to lower the pH (make it more acidic).

However, it’s generally not necessary to adjust the pH unless you’re composting highly acidic or alkaline materials.

7. Location, Location, Location: Choosing the Right Spot

The location of your compost pile can also affect the decomposers that are attracted to it. Choose a location that is:

- Shady: This will help keep the compost pile moist and cool.

- Well-drained: This will prevent the compost pile from becoming waterlogged.

- Accessible: This will make it easier to add materials and turn the pile.

- Near a water source: This will make it easier to water the compost pile.

Avoid locating the compost pile near structures or areas where odors could be a problem.

Specific Strategies for Attracting Different Decomposers

While the general principles above apply to all decomposers, there are some specific strategies you can use to attract particular types of organisms:

Attracting Bacteria

- Maintain a good carbon-nitrogen ratio.

- Ensure adequate moisture.

- Turn the compost pile regularly to aerate it.

- Keep the compost pile warm (thermophilic composting).

- Add a compost starter or activator to introduce beneficial bacteria.

Attracting Fungi

- Add woody materials (like wood chips or branches) to the compost pile.

- Maintain a slightly acidic pH.

- Avoid over-watering the compost pile.

- Leave some materials undisturbed for longer periods of time.

Attracting Worms

- Create a worm-friendly environment by providing a moist, dark, and sheltered habitat.

- Add plenty of food scraps, especially vegetable and fruit peels.

- Avoid adding acidic or spicy foods, which can harm worms.

- Protect worms from extreme temperatures.

- Start with a worm bin or add worms directly to your compost pile.

Attracting Insects

- Provide a variety of materials for insects to feed on.

- Maintain a moist, sheltered environment.

- Avoid using pesticides or herbicides near the compost pile.

- Tolerate the presence of insects, even if they seem undesirable (most are beneficial).

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Even with the best intentions, composting can sometimes present challenges. Here are some common problems and how to address them:

Problem: The compost pile smells bad.

Cause: Anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen).

Solution: Turn the compost pile regularly to aerate it. Add dry materials (browns) to absorb excess moisture. Avoid adding meat, dairy, or oily foods, which can contribute to odors.

Problem: The compost pile is not heating up.

Cause: Lack of nitrogen, moisture, or aeration.

Solution: Add nitrogen-rich materials (greens). Water the compost pile to maintain adequate moisture. Turn the compost pile regularly to aerate it.

Problem: The compost pile is too wet.

Cause: Excessive moisture or poor drainage.

Solution: Add dry materials (browns) to absorb excess moisture. Turn the compost pile to aerate it. Ensure the compost pile is located in a well-drained area.

Problem: The compost pile is attracting pests (flies, rodents).

Cause: Improper management or the presence of food scraps.

Solution: Bury food scraps deeply in the compost pile. Cover the compost pile with a layer of brown materials. Avoid adding meat, dairy, or oily foods. Use a compost bin with a lid to prevent pests from accessing the compost.

Problem: The compost is taking too long to decompose.

Cause: Improper carbon-nitrogen ratio, lack of moisture, or inadequate aeration.

Solution: Adjust the carbon-nitrogen ratio. Ensure adequate moisture. Turn the compost pile regularly to aerate it. Shred or chop materials before adding them to the compost pile.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Composting Techniques

Once you’ve mastered the basics of attracting native decomposers, you can explore some advanced composting techniques to further enhance your composting process:

Vermicomposting: Worm Power

Vermicomposting involves using worms to break down organic matter. This is a great option for indoor composting or for those who want to produce high-quality compost quickly. Red wigglers are the best type of worm for vermicomposting.

Bokashi Composting: Fermenting Your Food Waste

Bokashi composting is an anaerobic fermentation process that uses inoculated bran to break down food waste. This method can handle all types of food waste, including meat, dairy, and oily foods. The fermented material is then buried in the soil, where it decomposes further.

Compost Tea: Liquid Gold

Compost tea is a liquid extract made by steeping compost in water. It’s a great way to deliver beneficial microbes and nutrients to your plants. Compost tea can be used as a foliar spray or soil drench.

Conclusion: A Thriving Ecosystem in Your Backyard

Attracting native decomposers is the key to successful composting. By creating the right environment and providing the right conditions, you can transform your compost pile into a thriving ecosystem that produces nutrient-rich compost for your garden. Composting is not just about reducing waste; it’s about participating in nature’s recycling process and creating a more sustainable future. So, get out there, start composting, and let the decomposers do their magic!

Remember, patience is key. Composting takes time, and the results may not be immediate. But with consistent effort and attention, you’ll be rewarded with a valuable resource that will benefit your garden and the environment.