Creating a Native Plant Buffer Zone: A Comprehensive Guide to Protecting Your Land and Ecosystem

In an era where environmental consciousness is steadily growing, the concept of creating a native plant buffer zone is gaining significant traction. What exactly is a native plant buffer zone, and why should you consider establishing one? This comprehensive guide delves into the intricacies of native plant buffer zones, exploring their ecological benefits, practical implementation, and long-term sustainability.

What is a Native Plant Buffer Zone?

A native plant buffer zone is essentially a transitional area of native vegetation strategically planted and maintained between a developed or disturbed area and a more sensitive natural environment. Think of it as a protective shield, a green barrier designed to mitigate the negative impacts of human activities on vulnerable ecosystems. These buffer zones are composed exclusively of plant species that are indigenous to the local area, ensuring that they are well-adapted to the climate, soil conditions, and overall environment.

Unlike manicured lawns or ornamental gardens, native plant buffer zones are designed to mimic natural ecosystems. They incorporate a diverse array of trees, shrubs, grasses, and wildflowers, creating a complex and interconnected web of life. This biodiversity is crucial for the buffer zone’s effectiveness in providing a wide range of ecological services.

Why Create a Native Plant Buffer Zone? The Myriad Benefits

The advantages of establishing a native plant buffer zone are multifaceted and far-reaching. These zones offer a plethora of ecological, economic, and aesthetic benefits that contribute to a healthier and more sustainable environment.

Ecological Benefits: A Haven for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

- Water Quality Improvement: One of the primary functions of a native plant buffer zone is to filter pollutants from stormwater runoff. As rainwater flows through the dense vegetation, it is naturally filtered, removing sediments, excess nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus), pesticides, and other harmful contaminants. This filtration process helps to protect nearby streams, rivers, lakes, and wetlands from pollution, ensuring cleaner and healthier water resources. The root systems of native plants also stabilize the soil, preventing erosion and further reducing sedimentation.

- Soil Erosion Control: The extensive root systems of native plants act as a natural anchor, holding the soil in place and preventing erosion. This is particularly important in areas with steep slopes or unstable soils. By reducing erosion, buffer zones help to maintain soil fertility, prevent landslides, and protect water quality.

- Wildlife Habitat Creation: Native plants provide essential food and shelter for a wide variety of wildlife species, including birds, mammals, insects, amphibians, and reptiles. They offer nesting sites, foraging opportunities, and protection from predators. By creating a diverse and interconnected habitat, buffer zones can support thriving populations of native wildlife. The specific types of wildlife that benefit from a buffer zone will depend on the plant species used and the overall landscape context.

- Air Quality Improvement: Like all plants, native vegetation absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and releases oxygen through photosynthesis. This process helps to improve air quality by reducing greenhouse gas concentrations and mitigating the effects of climate change. Buffer zones also help to filter air pollutants, such as particulate matter and ozone, creating a healthier environment for humans and animals.

- Pollinator Support: Native plants are often specifically adapted to attract native pollinators, such as bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. These pollinators play a crucial role in the reproduction of many plant species, including agricultural crops. By providing a reliable source of nectar and pollen, buffer zones can support healthy pollinator populations, which are essential for maintaining biodiversity and food security.

- Flood Control: Native plant buffer zones can help to reduce the risk of flooding by slowing down stormwater runoff and allowing it to infiltrate into the soil. The dense vegetation acts as a natural sponge, absorbing excess water and preventing it from overwhelming drainage systems. This is particularly important in urban areas where impervious surfaces can exacerbate flooding problems.

- Temperature Regulation: The shade provided by trees and shrubs in a buffer zone can help to lower temperatures in surrounding areas. This is especially beneficial in urban heat islands, where temperatures can be significantly higher than in rural areas. By reducing temperatures, buffer zones can help to conserve energy, improve air quality, and enhance human comfort.

Economic Benefits: Investing in Long-Term Sustainability

- Reduced Maintenance Costs: Native plants are generally low-maintenance, requiring less watering, fertilizing, and pest control than non-native species. Once established, they are well-adapted to the local climate and soil conditions, making them more resilient and less susceptible to problems. This can translate into significant cost savings over the long term.

- Increased Property Values: Properties with well-maintained native plant buffer zones often have higher property values than those without. The presence of a healthy and attractive buffer zone can enhance the aesthetic appeal of a property, making it more desirable to potential buyers. In addition, the ecological benefits of a buffer zone can be seen as an added value, particularly for environmentally conscious buyers.

- Stormwater Management Cost Savings: By reducing stormwater runoff and improving water quality, buffer zones can help to reduce the need for expensive stormwater management infrastructure, such as detention ponds and treatment facilities. This can result in significant cost savings for municipalities and developers.

- Erosion Control Cost Savings: Preventing soil erosion can save money on repairs to infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, and buildings. Buffer zones can also help to protect valuable topsoil, which is essential for agriculture and other land uses.

- Potential for Revenue Generation: In some cases, buffer zones can be used to generate revenue through activities such as ecotourism, hunting, or sustainable harvesting of plant materials. This can help to offset the cost of establishing and maintaining the buffer zone.

Aesthetic Benefits: Enhancing Beauty and Tranquility

- Enhanced Visual Appeal: Native plant buffer zones can add beauty and visual interest to a landscape. The diverse array of colors, textures, and forms of native plants can create a visually appealing and dynamic environment.

- Increased Privacy: Buffer zones can provide a natural screen, increasing privacy and reducing noise pollution. This can be particularly beneficial for properties located near busy roads or other sources of disturbance.

- Improved Sense of Place: Native plants can help to create a stronger sense of place by reflecting the unique character of the local environment. They can also provide a connection to the natural history of the area.

- Opportunities for Recreation and Education: Buffer zones can provide opportunities for recreation and education, such as hiking, birdwatching, and nature study. They can also serve as outdoor classrooms for students of all ages.

- Reduced Stress and Improved Well-being: Studies have shown that spending time in nature can reduce stress, improve mood, and enhance overall well-being. Native plant buffer zones can provide a convenient and accessible way to connect with nature.

Planning Your Native Plant Buffer Zone: A Step-by-Step Guide

Creating a successful native plant buffer zone requires careful planning and execution. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you get started:

1. Assess Your Site and Define Your Goals

The first step is to thoroughly assess your site and define your goals for the buffer zone. Consider the following factors:

- Site Characteristics: Evaluate the soil type, slope, drainage, sunlight exposure, and existing vegetation. This information will help you determine which native plant species are best suited for your site.

- Adjacent Land Uses: Consider the land uses adjacent to your site, such as agriculture, residential development, or industrial areas. This will help you identify potential sources of pollution and other impacts that the buffer zone needs to address.

- Water Resources: Identify any nearby streams, rivers, lakes, or wetlands. The buffer zone should be designed to protect these water resources from pollution and erosion.

- Wildlife Habitat: Assess the existing wildlife habitat on your site and in the surrounding area. The buffer zone should be designed to enhance and expand this habitat.

- Desired Outcomes: What specific goals do you want to achieve with your buffer zone? Do you want to improve water quality, control erosion, create wildlife habitat, enhance aesthetics, or achieve some other objective?

2. Select the Right Native Plant Species

Choosing the right native plant species is crucial for the success of your buffer zone. Consider the following factors:

- Adaptation to Site Conditions: Select plant species that are well-adapted to the soil type, slope, drainage, sunlight exposure, and other site characteristics.

- Desired Functions: Choose plant species that will provide the desired functions, such as water filtration, erosion control, wildlife habitat, or aesthetic appeal.

- Plant Size and Growth Rate: Consider the mature size and growth rate of the plant species you select. Choose species that will be appropriate for the size of your buffer zone and that will not outcompete other desirable plants.

- Plant Availability and Cost: Check the availability and cost of the plant species you are considering. It may be necessary to adjust your plant selection based on these factors.

- Biodiversity: Aim for a diverse mix of plant species to create a more resilient and ecologically functional buffer zone. Include a variety of trees, shrubs, grasses, and wildflowers.

Consult with local native plant nurseries, conservation organizations, or extension agents for recommendations on appropriate plant species for your area.

3. Design Your Buffer Zone

The design of your buffer zone will depend on your site characteristics, goals, and plant species selection. Consider the following design principles:

- Width: The width of the buffer zone is a critical factor in its effectiveness. Wider buffer zones generally provide greater benefits. A minimum width of 25 feet is often recommended, but wider buffer zones may be necessary in areas with steep slopes, erodible soils, or significant pollution sources.

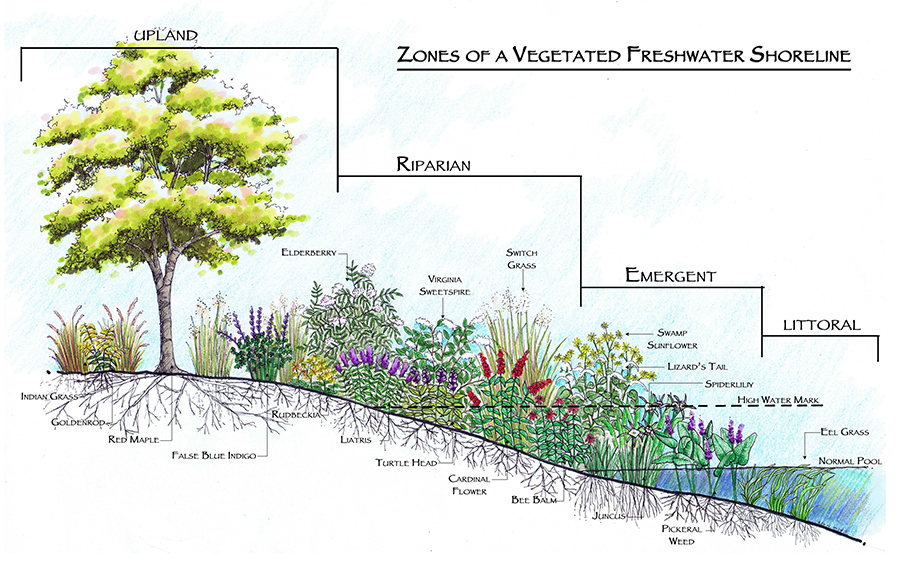

- Zoning: Consider creating different zones within your buffer zone to maximize its functionality. For example, you might have a zone of dense vegetation near the disturbed area to filter pollutants, a zone of taller trees and shrubs to provide wildlife habitat, and a zone of wildflowers and grasses to enhance aesthetics.

- Planting Density: Plant your buffer zone densely enough to provide effective cover and competition against weeds, but not so densely that it inhibits plant growth. Follow the planting recommendations for the specific plant species you are using.

- Planting Layout: Arrange your plants in a natural and aesthetically pleasing manner. Avoid straight lines and uniform spacing. Group plants of the same species together to create a more natural look.

- Access and Maintenance: Plan for access to the buffer zone for maintenance purposes, such as weeding, pruning, and trash removal.

4. Prepare Your Site

Proper site preparation is essential for successful plant establishment. Follow these steps:

- Remove Existing Vegetation: Remove any existing vegetation, such as grass, weeds, or invasive species. This can be done manually, with herbicides, or with a combination of methods.

- Amend the Soil: Amend the soil with compost or other organic matter to improve its fertility and drainage. This is particularly important in areas with poor soil quality.

- Grade the Site: Grade the site to create a smooth and even surface. This will help to ensure proper drainage and prevent erosion.

- Install Erosion Control Measures: Install erosion control measures, such as silt fences or erosion control blankets, to prevent soil erosion during the establishment phase.

5. Plant Your Buffer Zone

Plant your buffer zone according to the planting recommendations for the specific plant species you are using. Follow these tips:

- Plant at the Right Time of Year: The best time to plant is typically in the spring or fall, when temperatures are mild and moisture is plentiful.

- Dig the Right Size Hole: Dig a hole that is large enough to accommodate the root ball of the plant.

- Loosen the Root Ball: Loosen the root ball of the plant to encourage root growth.

- Plant at the Correct Depth: Plant the plant at the same depth it was growing in the nursery container.

- Water Thoroughly: Water the plant thoroughly after planting.

- Mulch: Mulch around the plant with wood chips or other organic mulch to help retain moisture, suppress weeds, and regulate soil temperature.

6. Maintain Your Buffer Zone

Regular maintenance is essential for the long-term success of your buffer zone. Follow these tips:

- Water Regularly: Water your plants regularly, especially during the first year after planting.

- Weed Regularly: Weed your buffer zone regularly to prevent weeds from outcompeting your native plants.

- Prune as Needed: Prune your plants as needed to maintain their shape and health.

- Fertilize Sparingly: Fertilize your plants sparingly, if at all. Native plants are generally adapted to low-nutrient soils.

- Control Pests and Diseases: Monitor your plants for pests and diseases and take appropriate action if necessary. Use environmentally friendly pest control methods whenever possible.

- Remove Trash and Debris: Remove any trash or debris from your buffer zone to keep it clean and attractive.

- Monitor Your Buffer Zone: Regularly monitor your buffer zone to assess its effectiveness and identify any problems.

Overcoming Challenges: Common Issues and Solutions

Creating and maintaining a native plant buffer zone can present certain challenges. Here are some common issues and potential solutions:

- Invasive Species: Invasive species can quickly outcompete native plants and degrade the quality of the buffer zone. Regularly monitor your buffer zone for invasive species and take prompt action to control them. This may involve manual removal, herbicide application, or other control methods.

- Deer Browsing: Deer can browse on native plants, particularly young seedlings. Protect your plants from deer browsing by using deer fencing, tree tubes, or deer repellents.

- Soil Compaction: Soil compaction can inhibit plant growth and reduce water infiltration. Alleviate soil compaction by aerating the soil or adding organic matter.

- Lack of Sunlight: If your buffer zone is shaded by trees or buildings, select shade-tolerant native plant species. You may also need to prune or remove some trees to increase sunlight exposure.

- Waterlogging: If your buffer zone is waterlogged, select water-tolerant native plant species. You may also need to improve drainage by installing drainage tiles or creating raised beds.

- Funding: Establishing and maintaining a native plant buffer zone can be expensive. Explore funding opportunities from government agencies, foundations, and other organizations.

- Community Support: Gaining community support is essential for the long-term success of your buffer zone. Educate your neighbors and community members about the benefits of native plant buffer zones and involve them in the planning and maintenance process.

Examples of Successful Native Plant Buffer Zones

Numerous successful native plant buffer zones have been established around the world. Here are a few examples:

- Chesapeake Bay Watershed: Extensive efforts have been made to establish native plant buffer zones along streams and rivers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed to reduce nutrient pollution and improve water quality.

- Great Lakes Restoration Initiative: The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has funded numerous projects to restore and protect coastal wetlands and riparian areas, including the establishment of native plant buffer zones.

- Urban Greenways: Many cities have created urban greenways that incorporate native plant buffer zones to provide recreational opportunities, improve air quality, and enhance biodiversity.

- Agricultural Buffer Strips: Farmers are increasingly using native plant buffer strips along fields to reduce soil erosion, improve water quality, and provide wildlife habitat.

The Future of Native Plant Buffer Zones

As awareness of the environmental benefits of native plant buffer zones grows, their use is likely to become more widespread. Native plant buffer zones are an important tool for protecting our natural resources and creating a more sustainable future. With careful planning, implementation, and maintenance, native plant buffer zones can provide a wide range of ecological, economic, and aesthetic benefits for generations to come.

By embracing the principles of ecological restoration and sustainable land management, we can create a world where native plant buffer zones are an integral part of our landscapes, contributing to a healthier and more vibrant planet.

Conclusion: Embrace the Power of Native Plants

Creating a native plant buffer zone is an investment in the health and well-being of your land, your community, and the environment. By choosing native plants, you are not only beautifying your surroundings but also contributing to the preservation of biodiversity, the improvement of water and air quality, and the creation of a more sustainable future. So, take the first step today and embrace the power of native plants to transform your landscape into a thriving ecosystem.